Tine Baanders was born on 4 August 1890 as the daughter of Lena van den Berg and Hermanus Hendrikus Baanders. Hermanus was a building contractor and architect during a period in which Amsterdam began to expand rapidly. Tine was the youngest of eight children—four boys and four girls. She was my great-aunt; I am the grandchild of Ambrosius (1883–1950), one of the four sons. Hermanus died relatively early, in 1905. His sons Herman and Jan continued the architecture firm. Herman, Tine’s eldest brother, became her guardian.

After Tine’s death in 1971, my mother secured the enormous quantity of letters, photographs and negatives she left behind. In total, these filled six moving boxes. She had begun investigating the contents, but did not get very far. At that time, I was getting into photography as a hobby and found the large, old-fashioned negatives especially interesting — they offered much room for experimentation with Photoshop and other editing software. Only after my retirement in 2009 did I have the time to dive into them properly — and discovered that the letters were essential to understanding the photographs.

Tine pursued various art studies in her youth, financed primarily by her two oldest brothers, Herman and Bertus. These were, successively: the Quellinus School of Arts and Crafts (1907–1909), the Day Drawing and Arts-and-Crafts School for Girls (1909–1910) in Amsterdam, the Kunstgewerbeschule in Zurich (1911), and finally the State Academy of Fine Arts (Rijksakademie) (1913–1917), again in Amsterdam. At her first school she was the only girl among boys and assumed that they were better. Nonetheless, she won first and second prizes. She travelled to Zurich with her friend Cateau (“To”) Berlage, daughter of the famous architect H.P. Berlage. Through that school, she also found her first job (1911–1912) as a draughtswoman at the Graphische Anstalt J.E. Wolfensberger (which would become famous a few years later for its posters promoting winter sports in Switzerland). Her family highly encouraged her to attend these schools.

Back in Amsterdam, she was commissioned to set up a “statistical drawing studio” for the exhibition De Vrouw 1813–1913 (The Woman 1813–1913), held in 1913 in Amsterdam to celebrate 100 years of the Dutch Kingdom. There, she came into contact with leading figures in the women’s movement: Rosa Manus first, later Aletta Jacobs, and even the American feminist Carrie Chapman Catt.

Homosexuality was never discussed in her milieu, but there was no shortage of male admirers — as evidenced by preserved letters. The first admirer who wrote to her (in 1910, when she was 19) began hopefully, but slowly grew disappointed because Tine would not “go further,” without explaining why. This pattern repeats itself in all subsequent correspondence with admirers. Tine herself does not seem to have understood why she did not wish to continue with any of these young men.

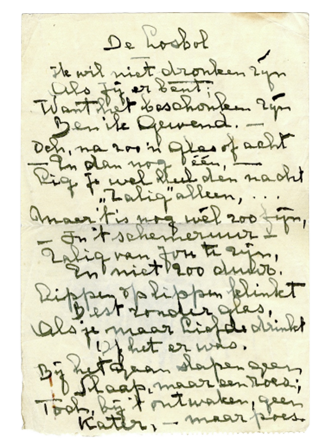

Upon graduating from the Rijksakademie in 1917, one of her teachers — painter and inventor Herman Hana — wrote on the back of a photograph “… in memory of much that never was.” He processed his frustration humorously in the poem De Losbol. Its final stanza reads: “When going to sleep, no / sleep but a thrill; / Yet when awakening no / hangover — but a puss.”

Around 1920, Tine befriended the painter couple Samuel “Mommie” Schwarz and Else Berg. Both were Jewish — he Dutch, she German. Soon, Else and Tine began sharing a bed. In 1922 they travelled through Italy for several months, together with a photographer from Berlin, Hanna Elkan. Later, in the 1930s, Hanna settled in Amsterdam, where she became known for her portraits of actors, writers and other artists. Else painted during the journey, Tine studied medieval books and manuscripts, and Hanna made photo reports. Whether Hanna participated in Tine and Else’s sexual activities is not evident from the sources.

Tine did not connect her relationship with Else to her repeated rejections of male suitors. Apparently the right man simply had not appeared yet. Around age thirty, circa 1920, her family began to worry. All seven of her siblings were now married. Her eldest brother Herman explained to one of Tine’s friends what kind of man he believed she needed:

Tine must be taken along; it must be a chap — one who simply takes her, that is how it must be. They must not ask hesitantly; they must take her. ”

– Herman, Tine Baanders’ eldest brother

Here, Herman seems mostly to be describing his own self-image.

From 1917 to 1921, an extremely close friendship developed between Tine and this friend, Heleen Dijkgraaf. She was the wife of Anton Dijkgraaf, director of the Rotterdam Drydock Company and the client who had commissioned Tine’s brothers Herman and Jan to build a garden village for the shipyard’s workers: the garden village Heijplaat. The letters clearly reveal that Heleen was heterosexual — she had five children of her own and one foster child — and that she became Tine’s dearest friend. Their very intimate correspondence sometimes comprised two letters a week, though they saw each other in person as well. More than 60 letters have survived. Heleen died very suddenly in 1921. After her death, her husband Anton returned to Tine the letters she had written to his wife. When dated alongside the letters written in the other direction, these provide fascinating insight into how they lived and thought.

Brother Herman also supervised the renovation of the Dijkgraafs’ second home near Uddel on the Veluwe. A secret love developed between Herman and Heleen. Heleen wrote to Tine, at first hesitantly:

… if I give in, we’ll be playing with fire … But a bit of fireworks is also so delightful! ”

– Heleen Dijkgraaf on the love affair

Ultimately, this became a passionate affair. The lovers once met in Tine’s upstairs apartment in Amsterdam, while Tine temporarily left the house. Anton never found out. Among Herman’s grandchildren, however, this and other escapades are well-known.

Heleen evaluated Tine’s suitors but disapproved of all of them. They included well-known names, and all were married men: Richard “Rik” Roland Holst (director of the Rijksakademie during Tine’s time there), his nephew Adriaan “Jany” Roland Holst (the famous poet), Herman Hana (the aforementioned teacher at the Rijksakademie, painter, inventor), and even Michel de Klerk (renowned architect of the Amsterdam School). The end of the affair with Michel de Klerk is described by Tine in a January 1920 letter to Heleen (“S.” refers to Sam — Michel de Klerk’s nickname — who was married to Lea Jessurun):

In between everything, the love play with S., which had begun as such a deep and tender friendship, came to pass again a week ago [and has now ended, AB] – It is sad, very sad for him! And I wish I could be as sorrowful as he is! But I could not keep it up any longer, and he, poor fellow, even less! I perhaps should have realized it sooner, because now I have caused someone much grief [sic, AB]. The boy is shattered. And I truly cannot help it, Heleen … ”

– Tine Baanders on Michel de Klerk

Two years later, in 1923, Tine fell in love with “Teun” Timmner. Teun (Hermana Catherina) was the stepdaughter of Bas Veth, a plantation owner who had become wealthy in the Dutch East Indies. As a girl she travelled to fashionable tourist destinations such as Menton and Zermatt, and was therefore accustomed to a life of luxury. She was five years younger than Tine but already had sexual experience with women. I suspect that Teun showed Tine that marrying a man was not necessary at all, and that she could have female partners. From that point, things became much clearer for Tine. The family also accepted this quite readily. When, several years later, Herman and Françoise’s second son, Herman Jr., came out, his parents were loving and supportive.

What stands out in these stories is how often extramarital affairs occurred — and not only secretly. Temporary partner-swapping was often visible to others, along with the occasional jealousy and quarrels that came with it. Openness about such matters seems to have been greater on the homosexual side than on the heterosexual side.

A charming example of a lesbian romance of Tine’s, visible to Teun, is her affair with Ellen Kramer, eldest daughter of Piet Kramer — one of the leading Amsterdam School architects, known for the many bridges he designed in Amsterdam and for the Bijenkorf department store in The Hague. Ellen was trained as a pianist. When Tine and Teun, together with another lady, departed for a road trip to Norway in the summer of 1930, Ellen (then 18) wrote Tine a letter. In it, she wrote passionately:

I have kept your handkerchief. It smells so wonderfully of your hair. ”

– Ellen Kramer

She proposed that they travel to Italy together the following year. And indeed, this happened — in Tine’s Amilcar, to Genoa, where Tine’s sister Mien and her husband Wim Schimmel lived; he was the brother of my grandmother. The journey continued to a villa in Théoule-sur-Mer on the French Riviera, rented by Teun, where Teun had brought her friend Dora Castell. Dora was a German painter living in southern France; in 1933 she moved to Amsterdam and moved in with Tine — where she remained until the early 1960s.

A highly romantic scene from this journey appears in another photograph, taken by Ellen Kramer in August 1931. We see Teun (left) and Tine on the terrace of the villa, overlooking the Bay of Cannes. The photograph was taken by Ellen, who wrote on the back:

Teun sings her morning song to Tine! “proprio bella!”

It means, of course, that she is the most beautiful. And apparently this was a ritual every morning. Could it be more romantic?

Ellen (by then 19) thus made a picture of her beloved, who was being serenaded with love by the woman who had made her discover what love between women could be. And she wrote the explanation on the reverse side. This was in 1931. These women were far ahead of their time.

My mother, who met my father and the rest of his family in 1938, told me that, in her view, Teun and Dora alternated being in Tine’s favour, with fierce competition between them. Undoubtedly, this happened at times, but based on the sources, I believe they also often moved as a trio. The letters reveal little of quarrels, though that is, of course, to be expected. Even after Tine openly came out as lesbian, a few disappointed male admirers ended their relationships with reproach. But this likely affected Tine very little.

From 1919 to 1955, Tine taught at her former school, the Day Drawing and Craft School for Girls, which later merged into the Institute for Arts and Crafts Education (IvKNO) and, in 1968, became the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. This meant that she could rarely travel outside the school holidays; she would first have to arrange and pay for her replacement. For this reason, most of her major trips through Europe took place in July and August. Teun had no job and therefore no such limitations.

Tine had no examples of homosexuality in her childhood, nor did her family. Teun evidently helped her to understand herself, enabling her to ‘come out.’ Because she was open about it, everyone understood, making life much easier. When Herman junior came out in the 1930s, his parents were very understanding. Tine had paved the way for him.